A New York Times article published last week explores the recent uptick in attrition within police forces. Public confidence in police fell to 48% last year, a 27‐year low, and police have reported that the loss of confidence has made it more difficult to do their jobs. Now, the fallout has hit retention rates, as police forces struggle to keep officers committed to a difficult profession that has undergone a reputational fall from grace. The article ends with an officer describing her feelings about her relationship with the public as akin to being dumped without knowing why.

It’s a striking analogy, and the sentiment is likely shared by many police officers. A survey of police officers from 2017 revealed that just over two‐thirds of officers felt that highly publicized incidents of police violence were isolated incidents. It’s not hard to see how good cops feel they’ve been judged guilty by association.

But one solution to this problem is simple: Stop protecting the guilty officers.

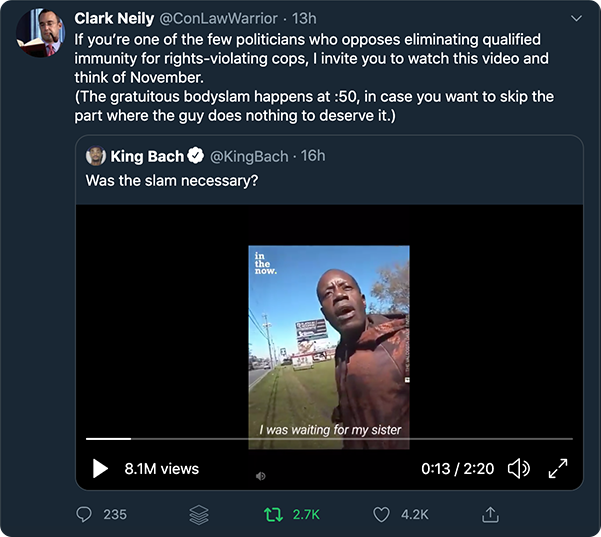

Consider the headline of the Minneapolis Police Department press release issued hours after George Floyd’s death: “Man Dies After Medical Incident During Police Interaction.” If not for the bystander footage and overwhelming public response, would Derek Chauvin—who already had 17 complaints against him before he murdered George Floyd—have been held to account for his actions?

Compare George Floyd’s case to the death of Tony Timpa in 2017. Timpa called police during a mental episode that left him scared for his life. The officers held Timpa down, kneeled on his back, and mocked him as he screamed “help me” between agonal breaths. He was declared dead 14 minutes later.

Tony Timpa’s case made the local news, but it never reached a national profile. The officers mounted a vigorous legal defense to his family’s civil rights lawsuit, asserting the judge‐made defense of qualified immunity, which requires plaintiffs to identify a preexisting case with nearly identical facts. The trial judge held that the officers were entitled to qualified immunity and dismissed the case because there was “no binding authority from either the Supreme Court or the Fifth Circuit holding that prone restraint… is a violation when performed in the manner of Defendants’ restraint of Timpa.” Every single one of the officers kept their jobs, including the one who joked that Tony needed to wake up for school as the police watched him die.

The lesson from the George Floyd and Tony Timpa killings is this: While police departments are loath to get rid of the proverbial bad apples, they sometimes prove responsive to overwhelming public pressure. And there are few things in criminal justice that garner more universal support among the public than the need for stronger accountability for police officers: Over 96% of Americans support changing management practices so officers are actually punished for misconduct, and 98% would support preventing officers responsible for multiple abuses of power from continuing to serve. All too often, however, police departments take the opposite approach. A survey of over 323,000 allegations of police misconduct in New York, for instance, revealed that less than 3% of the complaints resulted in any kind of penalty for the officers. Only 12 of those penalties (less than .0004% of the complaints) were terminations.

The most benign explanation for the knee‐jerk reaction of police departments to hide abuses of power is that the departments, recognizing that they need the public’s trust to operate, seek to avoid censure for bad acts in the most efficient way possible: by covering them up. But papering over a crumbling foundation cannot cure the cracks underneath. As departments allowed bad cops to survive—and thrive—Americans took notice. And while things may have reached a breaking point with the death of George Floyd last year, the reality is that confidence in American police has been trending downwards for nearly half a decade.

We cannot expect this situation to change if policing does not change, and one way to change officer behavior is to completely eliminate the doctrine of qualified immunity. Letting citizens enforce their rights against police would reduce the question of how police police themselves to a straightforward financial decision. If officers with track records of misconduct weren’t immune from lawsuits for the damages they caused, it’s highly unlikely that police departments would remain eager to keep them on the force—because they’re usually stuck with the bill. (And no, this would not mean police officers are exposed to lawsuits for split‐second mistakes—it would mean police are no longer immune from being sued for use of force that’s unreasonable under the circumstances).

What will not work is for police departments to continue relentlessly defending the proverbial bad apples while assuring citizens that they represent only a small fraction of all cops on the job. This strategy may have helped delay the collapse of American confidence in police, but we are well past the breaking point now.

The right way to rebuild public trust is to ensure that bad cops like Derek Chauvin are consistently held accountable for misconduct, and not just when they are caught on a video that happens to go viral. Police cannot do their jobs effectively—or happily—without public trust. And make no mistake—we need effective police with good morale and strong community rapport. But in order to get there, the bad cops have got to go.

David McMillan, a research intern with the Cato Institute’s Project on Criminal Justice, contributed to the development of this piece. David holds a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from The College of New Jersey. He is currently pursuing his MPP from the University of Edinburgh as a Saint Andrew’s Society Scholar.